By Asanga Abeyagoonasekera and Qamar Cheema

Of late, nearly 220 million people in Pakistan have experienced blackouts due to the country’s aggravated economic crisis. While multiple power plants were built under the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), the Chinese have now left due to debt non-payment, leaving a power shortage. So far, Pakistan has failed to pay $1.5 billion to the Chinese, citing a lack of foreign reserves.

Elsewhere, Sri Lanka’s debt to GDP ratio is 119% (Pakistan’s is at 70%). Unsustainable debt has triggered economic crisis in both nations. Pakistan’s foreign reserves are around $4.3 billion, enough for only the next two months. In Sri Lanka, an energy crisis triggered by foreign reserve shortages was followed by a food crisis, prompting a public uprising. Pakistan appears headed in the same direction. Agricultural production in Sri Lanka was directly impacted when President Gotabaya introduced an overnight switch from chemical to organic fertilizer. In Pakistan, the recent floods destroyed eight million acres of crops leading to food insecurity.

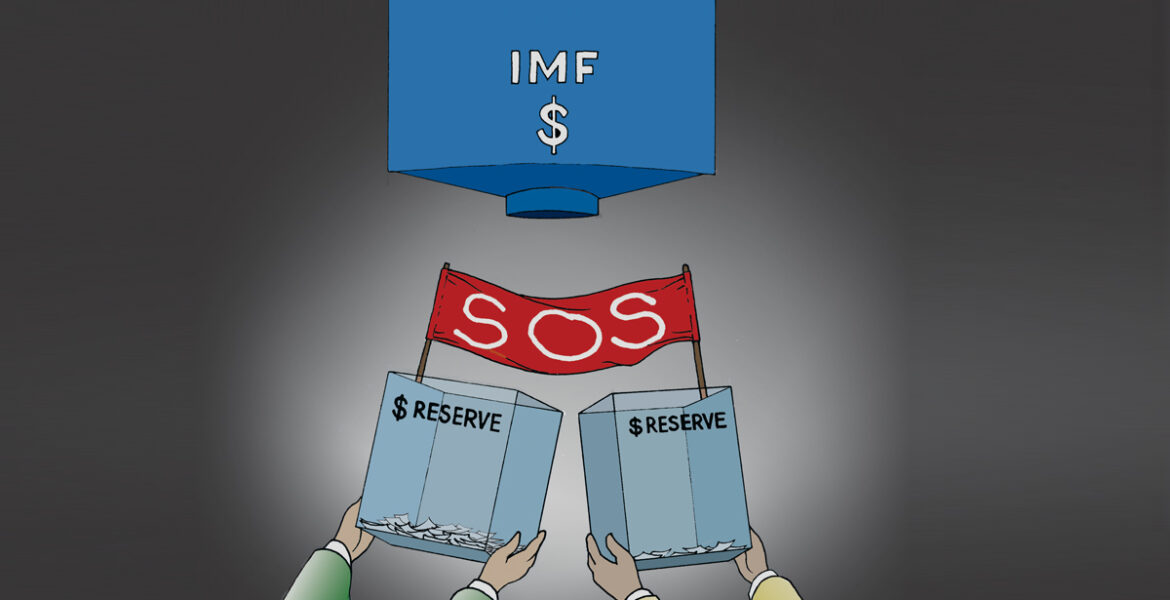

Months ago, Sri Lanka reached out to the IMF for $2.9 billion to stabilize its economy. Pakistan has likewise sought IMF assistance of $7 billion. While both countries had reached out to the IMF multiple times (Sri Lanka 17 times and Pakistan 23 times) before, this time seems different. China refused requests from both countries to restructure debt, only agreeing to a moratorium of two years for Sri Lanka. Pakistan was not able to obtain a moratorium but was given the opportunity to borrow and additional $2 billion.

Under President Xi, China has stressed shared growth and common prosperity. This has focused on business, trade, and economic development, and ignored global values of democracy, freedom of speech, and human rights. The China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) under the belt and road initiative (BRI) was seen by Pakistan’s political class and military as signaling trust in its leadership and a return to normalcy in the country after years of military operations against terrorists. Politicians remained under pressure from the military for bad governance, and the hoped for job creation did not take place. In addition, these projects have proven to be not self-sustaining, requiring continued public subsidies.

In Sri Lanka, BRI was endorsed by former President Mahinda Rajapaksa and continued by the subsequent governments, promising thousands of jobs, and substantial financial returns. None has materialized, and projects such as Hambanthota port, Mattala airport, a port city in Colombo, and the tallest tower in South Asia (the “Lotus tower” with a revolving restaurant) have barely generated any revenue. Some infrastructure remains as “ghost airports” without any flights and scarcely any investment in port city land in Colombo.

Former Pakistani Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif participated in the One Belt One Road summit in 2016 to approve a long-term plan for a $60 billion China Pakistan Economic Corridor. In the CPEC project, thousands of acres of agricultural land were to be given to Chinese enterprises for projects ranging from introduction of new seed varieties to innovative irrigation technology to allow industrial-scare farming. Other aspects of the CPEC included extensive projects for cities, new highways from Peshawar to Karachi, visa-free entries for Chinese nationals, investments in fiber optics, and investments in mining and minerals. Other high profile plans included building Gwadar port, making wineries and developing coastal tourism.

In Pakistan, the military was the primary stakeholder in CPEC because of its influence in the political and institutional arena. Politicians created a consensus that CPEC projects and Chinese investment were in the national interest, stifling questions from sceptics. Average Pakistanis facing energy shortages and poor infrastructure remained silent on the terms and conditions on which this foreign direct investment was coming into Pakistan. The Army raised two security divisions to protect Chinese businesspeople and projects from terrorist organizations. The government deployed more than 15,000 military personnel in the Special Security Division (SSD). The SSD provided security to 34 projects, whereas Maritime Security Force (MSF) provided security to coastal area projects. There is no information on how much this additional security costs. The Pakistani Army and Navy have been getting funds from these projects to provide protection, but Chinese workers have been killed and targeted by Baloch separatists and Tehreek e Taliban Pakistan (TTP). The Chinese offered to bring its private security, but Pakistan refused this offer.

In Sri Lanka, unlike Pakistan, it was the political elites who prioritized the BRI projects. Similarly, there was no transparency in Sri Lanka’s BRI projects; the public has yet to see the Hambanthota lease agreement nor the port city agreement, which was never discussed in parliament nor taken public comments. There was no stakeholder engagement and proper due diligence, and the feasibility of the projects was never assessed due to political influence. Above all, significant corruption concerns in many of these projects could never be investigated due to Chinese influence in Sri Lanka.

In Pakistan, loans to Pakistan from the Chinese government and Chinese banks were at 3.76% interest, whereas Western financial institutions provided financing for development projects at around 1 %. In Sri Lanka, some loans were taken at 6.5% for Hambanthota port. The maturity period of the Pakistan loans is 13.2 years, and the grace period is 4.3 years, whereas the same loans to France and Japan are at 1.1 % with a repayment of 28 years. In both countries, the real challenge for parliament, media, civil society, the political class, and bureaucracy has been the lack of a clear understanding of the terms and conditions of the BRI projects. Federal ministers or concerned ministers who dealt with loans and projects have yet to utter a single word in the presence of the media about the terms and conditions of Chinese loans. A typical response has been that the national interest will be compromised by disclosing details, adding that the Chinese do not like contracts to be made public. Pakistan’s incumbent foreign minister said, “loans from China are the price of development.” According to Pakistan’s Ministry of Finance, Pakistan’s debt to China exceeds $14 billion, the highest to any country. Independent sources say the debt could exceed $ 30 billion.

Comparatively, Sri Lankan debt to China is less than Pakistan, close to $10 billion, with some economists estimating it as high as $20 billion. China has gone to great lengths to counter criticism of its debt policies, including funding foreign think tanks to create a positive image. In addition, there is a more comprehensive strategic trap China has managed to install in countries like Sri Lanka and Pakistan. The “strategic trap” is orchestrated in three principal areas: political funding by CCP; human rights support to repressive regimes; and military assistance.

CPEC had provided hope for recipients as the Chinese heavily invested in infrastructure and the energy sector. In Pakistan, hoped-for economic zones for manufacturing and export have yet to be established. Gwadar port is still dysfunctional and electricity is coming from Iran for this project. Locals have migrated from the project site because of securitization and Chinese dominance in projects which marginalized the local Baloch population. Increased Chinese presence has given rise to the right-wing Islamist party Jamat I Islami in Gwadar. People have demonstrated under the leadership of right-wing Islamic cleric Hidyat Ur Rehman, who questioned the federal government and security institutions for unnecessary security check posts and for depriving small fishers of opportunities. Chinese investors had to close a wine factory because of Islamist pressure and protests. The rise of Islamist influences in Baluchistan, stagflation, corruption in Chinese projects, absence of transparency, marginalising of locals, the resurgence of terrorist activities and merger of Islamist and Baloch militants, and failure to revive the economy are some of the troubling realities of CPEC.

The BRI projects in Sri Lanka and Pakistan have similar patterns, raising questions of transparency, lack of due diligence, opaqueness, corruption, and heavy political-military influence. While BRI is not the only reason for the crises facing these countries, China could be identified as a considerable concern in Sri Lanka and Pakistan. Both cases are good examples of other BRI nations that have borrowed with little to show for it.